-

The Disturbing History Of Kuru, The Fatal Brain Disease Caused By CannibalismBy Morgan Dunn | Edited By Jaclyn AnglisPublished December 28, 2021Updated January 1, 2022

At its peak in the 1950s and ’60s, the kuru epidemic nearly decimated the Indigenous Fore people of Papua New Guinea.

Until the 1930s, no outsiders knew that the Fore people of Papua New Guinea even existed. In one of the world’s least-explored regions, the Fore had lived independently for years, developing a distinctive culture with traditions unknown even to their fellow islanders. One of these traditions was ritual cannibalism, which led to a widespread disease called kuru.

Australian gold prospectors were the first outsiders to make contact with the Indigenous people who lived in the eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea. The gold prospectors were soon followed by researchers and officers who patrolled the area. But it would take more than 20 years for the Fore’s cannibalism to come to light, along with its terrible consequences.

To the Fore, cannibalism was meant to be an act of love and grief — because they ate the bodies of their dead loved ones. But despite their intentions, this ritual was viewed with horror by most other groups of people around the world. And the aftermath of this practice was just as horrific.

The Fore’s consumption of dead people directly led to the spread of kuru. Also known as the “laughing death,” kuru is a fatal brain disease that causes victims to lose control of their emotions, limbs, and bodily functions. Disturbingly, many victims suffer from uncontrollable fits of laughter — and die less than a year after first showing symptoms of the disease.

At its peak in the 1950s, kuru was wiping out two percent of the tribe per year. While both the Fore and outside researchers realized that there was a major problem, they had no idea what was causing the laughing death epidemic at first. But before long, everyone learned the terrible truth.

Inside The Origins Of The Kuru Disease

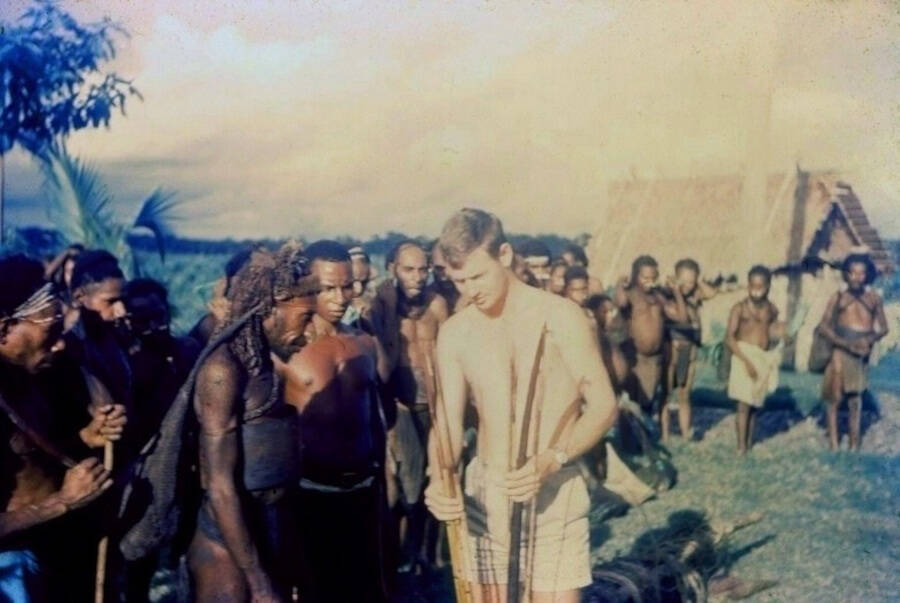

Wikimedia CommonsPapua New Guinea is inhabited by hundreds of distinct groups, some of which practiced cannibalism in the past.

Papua New Guinea is renowned for its hundreds of Indigenous groups left untouched by outside civilizations for thousands of years. In their homes nestled among the dense forests that blanket the country’s mountains, these groups developed a distinctive range of cultures and practices.

It wasn’t until the 16th century that Portuguese and Spanish explorers first touched down on the region. And even then, they only made contact with those who were living on the coasts. So, many Indigenous groups remained uncontacted by people from other countries until well into the 20th century.

Some of the more remote groups — like the Fore — practiced cannibalism. Though each tribe approached the ritual differently, the Fore firmly believedthat it was a sacred funerary rite. So, every time a person died, their body was cooked and eaten by their loved ones. The Fore people thought this ritual would tame the spirit of the dead body, and honor the deceased.

One medical researcher explained the Fore philosophy as such: “If the body was buried it was eaten by worms; if it was placed on a platform it was eaten by maggots; the Fore believed it was much better that the body was eaten by people who loved the deceased than by worms and insects.”

Wikimedia CommonsAustralian patrol officers were some of the first to notice the spread of kuru among the Fore.

It was usually women who were tasked with eating the person’s body — because it was thought that their bodies could handle housing a “dangerous” spirit. They would eat nearly every piece of “meat” and organ in the body except for the gallbladder. Crucially, this included the brain. However, women would sometimes feed “snacks” from the corpses to their young children. So, it was mostly women and children who were affected by kuru.

Though missionaries and colonial officials condemned cannibalism among the tribes who practiced it, the ritual remained widespread among groups of Fore. It’s unknown exactly when the kuru disease first appeared among them. But some researchers believe it first arose around the 1910s or 1920s, just a few decades before they made contact with outsiders.

This is supported by the lack of mentions of the disease in Fore histories, and because the Fore themselves recognized that the disease was depleting their population. If they had lived with kuru for generations, there would have likely been no Fore left. But by the time they encountered Australian and American researchers in the 1950s, they still numbered up to 11,000 people.

The problem facing both the Fore and researchers was that no one knew what kuru was or how it spread. But they did know the laughing death had become an epidemic, killing up to 200 people per year. While researchers thought contaminants or genetics may have caused the disease, the Fore people thought it was men who were practicing “sorcery.” But it wasn’t until the early 1960s that researchers were finally able to figure it out.

How Ritual Cannibalism Caused The Laughing Death Epidemic

Wikimedia CommonsA young victim of the laughing death epidemic, who is unable to stand without help.

Anthropologist Shirley Lindenbaum and her then-husband Robert Glasse were among the scientists involved in the first dedicated study of kuru in 1961. Traveling from village to village in the Fore community, they examined possible causes of the disease. After ruling out contaminants, they soon realized the disease wasn’t genetic either, because it affected women and children in the same social groups, rather than the same genetic groups.

But then, during their second visit, a New Zealand neurologist and epidemiologist named Dr. R.W. Hornbrook posed a key question: “What is it that the adult women and the children of both sexes in the Fore tribe are doing that the adult men are not?” The answer soon became clear: They were practicing cannibalism on their dead loved ones at funerals.

Though some experts remained skeptical, Lindenbaum and her colleagues persisted, finally prompting a group at the U.S. National Institutes of Health to test their theory. The researchers injected samples of infected human brains into chimpanzees. When the chimpanzees began to demonstrate signs of kuru months later, Lindenbaum’s hypothesis was vindicated.

But even though the central question of what caused kuru had been answered, there were still some holes to fill in. After all, the Fore were far from the only group to ever practice cannibalism throughout history, but they were the first known to experience such a disease. So, what exactly had sparked this unusual illness among the Fore but not other tribes?

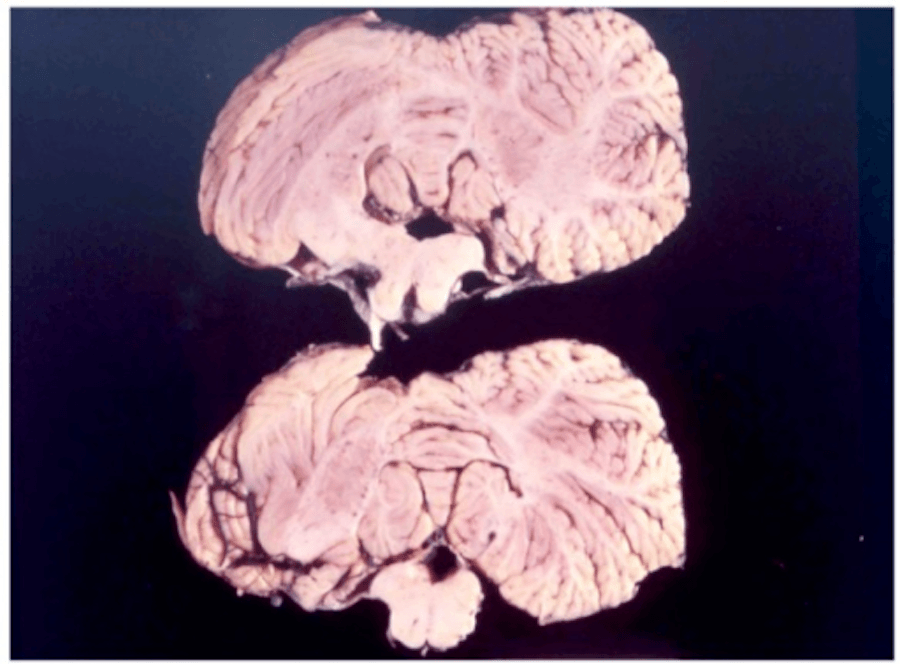

Wikimedia CommonsThe cerebellum of a kuru victim during the laughing death epidemic.

Since the Fore had mostly stopped practicing cannibalism by the 1960s — especially when they learned the dire consequences — it was tough to say exactly what had caused the laughing death epidemic. However, many experts believe it started after one Fore person developed a neurological condition called Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, which is similar to kuru.

Both illnesses are caused by prions, which are abnormal proteins that fold in an unusual way, forming lesions in the brain and causing profound damage to the nervous system and eventually the rest of the body. Both diseases are also fatal and often cause death about a year after symptoms first emerge.

Researchers have theorized that the member of the Fore who developed Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease had died sometime before the 1910s or 1920s. When this person’s body was eaten, the prions in their brain tissue spread to those who’d eaten them, who in turn passed the disease on to those who ate them. Without the benefit of modern medicine, the Fore were left with no clue as to what was killing hundreds of them for decades.

Little did they know that it was their ritual consumption of brains.

When The Kuru Epidemic Finally Ended

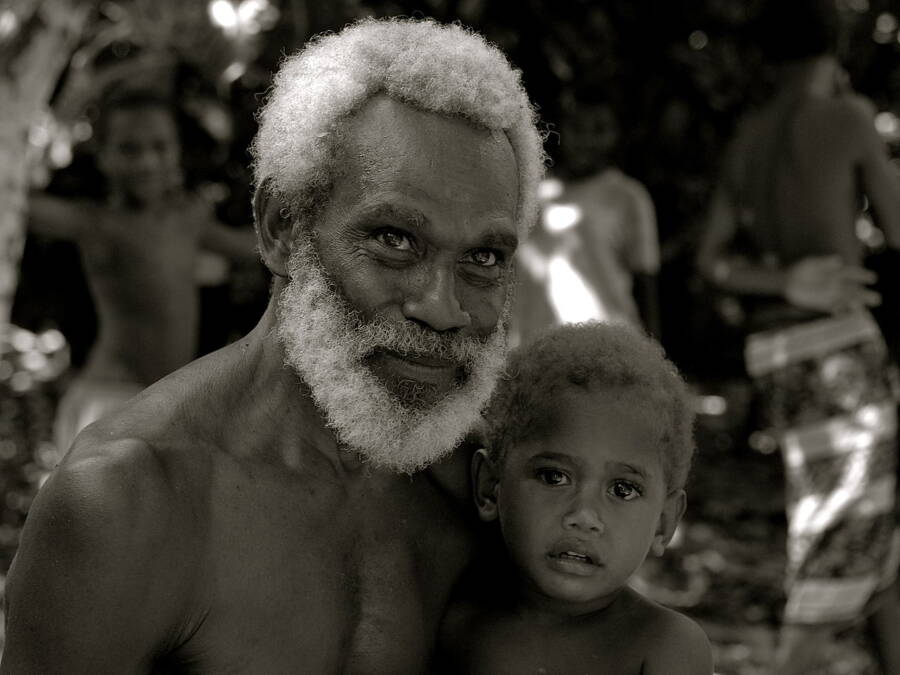

Wikimedia CommonsThe Fore people, like other Indigenous tribes in Papua New Guinea who once practiced cannibalism, are still around today and have since recovered from the kuru epidemic.

The number of kuru cases among the Fore gradually dwindled over the years after the researchers’ discoveries. However, the cases didn’t disappear immediately, as the disease sometimes took decades to show its effects.

According to Michael Alpers, a medical researcher at Curtin University in Australia who studied the disease, the last kuru victim died in 2009. And the epidemic was officially declared over among the Fore people in 2012.

Today, the Fore number about 20,000 people — which is nearly double the number of people who were around during the height of the kuru epidemic. The Fore are thrilled with their population growth, especially since the number of women and children is in a steady place once again.

As for the researchers, those who worked on the chimpanzee experiment were awarded a Nobel Prize for their findings. The knowledge gained from the research led to further breakthroughs in understanding illnesses such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (or “mad cow disease”), and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Most recently, researchers found that even though the Fore’s past custom of funerary cannibalism led to tragedy, it also resulted in a unique adaptation. In 2015, experts discovered that some Fore had developed a gene that protects them from kuru as well as other prion diseases like mad cow. And it may even protect them from some forms of dementia.

While they’re unlikely to return to the grisly customs of their ancestors, today’s Fore can be thankful that the unintended consequence of a long-held ritual now offers a positive trait that may hold the key to defeating some of humanity’s most debilitating neural conditions.

- Home

- Current Events

- Research/Education

- Memes Gallery 1

- Articles

- Recommended Reading

- Knightspirit Store

- Site Search